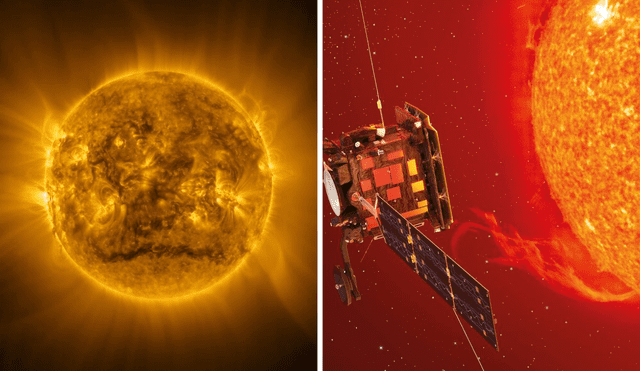

Solar Orbiter captures first-ever images of the sun’s south pole, revealing magnetic turbulence

ESA and NASA have looked at the sun's south pole for the first time and gathered possible indications of a shift in magnetic polarity.

For the first time, scientists now have a direct look at the sun’s south pole thanks to Solar Orbiter, a collaboration between ESA and NASA. The striking images, taken earlier this year and released this week, provide a view of an area of the sun that had never been easily examined before.

The moment is important because the sun is nearing the peak of its activity cycle that repeats every 11 years. ESA's science director Carole Mundell said that understanding how the sun works is not only interesting, but incredibly important. Solar storms and magnetic eruptions from our closest star can disrupt satellites, communications and power grids on earth.

ALSO SEE: Watch Mount Etna eruption: Pyroclastic flows, ash clouds, and tourist evacuations in Sicily

Rare magnetic behavior seen near the sun’s pole

What Solar Orbiter found was a surprise, a mass of magnetic fields with opposing polarities forming near the south pole a feature only found during solar maximum. It's also the time in the solar cycle when the sun's magnetic field is preparing to flip, although the mechanics of the flip are still not fully understood.

In the last few cycles, typically after the flip, one magnetic polarity begins to dominate again, settling the sun into a quieter phase. Researchers had the opportunity to witness the transition at exactly the right moment. "We're in the right place at the right time," said Sami Solanki, who heads the team that operates the probe's magnetic field array.

A new orbit, a fresh view of our star

Prior investigations predominantly viewed the sun from the same angle—the equator, as they orbit at Earth's equatorial plane. On the other hand, Solar Orbiter was launched into an orbit that would take it directly out of the equatorial plane. By using Venus for a set of gravity assists, the spacecraft has tilted its orbit a little bit at a time to the point of ultimately allowing it to look, "over the shoulder" of the sun to observe latitudes higher than the equator.

In March, it got itself just above the sun's equatorial plane—since the strict level is impossible, it positioned itself between 15 and 17 degrees from the equatorial plane, which permitted it to acquire new observations of the sun that are unprecedented. And it is only just starting. Over the next few years, as the spacecraft's orbit continues to tilt, the rate and degree of sun observations will increase greatly as the spacecraft will get a clearer look at the sun's poles. Daniel Müller of ESA articulated it well when he said, "We are on the edge in discovering much more about how the sun shapes space weather and how it impacts the solar system."